This is the thirtheenth entry in my series of thumbnail reviews of films I’ve been watching on the Criterion Channel streaming service since September 2021. I watched this set of ten films from the end of June till end July 2022.

This latest set of films include two classics from the British filmmaking duo Powell & Pressburger, a beautifully shot romantic drama from Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar-Wai, an indie crime drama directed by Paul Schrader, a classic Western pairing James Stewart and Marlene Dietrich, a Japanese family drama starring the incomparable Setsuko Hara, a WW2 spy thriller from legendary director Fritz Lang, a Japanese-set film noir from indie director Samuel Fuller, a fictionalized account of the great Chicago fire of 1871 and a dark psychological thriller starring Gene Tierney.

Light Sleeper (1992): Paul Schrader emerged in the 1970’s as the enfant terrible of American cinema, with his hard-edged, male-oriented scripts for leading directors like Sydney Pollack, Martin Scorsese and Brian de Palma. He hit the headlines during the 80’s for writing or directing controversial films like American Gigolo, Patty Hearst and The Last Temptation of Christ. From the 90’s, he entered a mellow phase, starting with this drama/thriller, Light Sleeper. Willem Dafoe plays John LeTour, a drug dealer working for a woman (Susan Sarandon) with a high class clientele. After years in the drug business, LeTour has become a jaded lost soul, living with insomnia (hence the film’s title) and experiencing a midlife crisis. A chance encounter with his ex-wife rekindles some of his old spark and a longing for a better life. But it’s not so easy to escape his circumstances, and LeTour becomes embroiled in a series of events beyond his control. Willem Dafoe infuses every scene with LeTour’s existential pain, and forms the emotional core of this sombre film. Schrader followed up Light Sleeper with a series of middling films for the next 25 years, and then made something of a comeback after 2017, directing three well-regarded films all featuring conflicted “lone wolf” men – First Reformed, The Card Counter and Master Gardener.

Ministry of Fear (1944): This spy thriller set in England during World War II comes with amazing credentials – directed by Fritz Lang, based on a novel by Graham Greene and starring Ray Milland. I found the storyline to be quite convoluted and somewhat far-fetched, making the entire viewing experience feel like something of a chore. I am not even going to attempt to summarize the film, except to say that it involves a palm reader at a fête, a medium at a séance, a blind man who is not blind, a “Macguffin” in the form of a cake, and exploding bombs. It wasn’t really my cup of tea. Apparently director Lang apologized to Graham Greene for the liberties that the film’s script took with his novel. On the other hand, the BFI has included this film in its list of Top 10 film adaptations of Graham Greene’s stories, so clearly it has some merits. A year later, actor Ray Milland would go on to win the Best Actor Oscar for his best known role, as the alcoholic writer in The Lost Weekend.

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943): This film was the first colour production from the celebrated British filmmaking duo of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, in the early years of their incredibly fertile creative period spanning the 1940’s. Featuring pioneering technicolor cinematography, it is considered one of the greatest British films ever made. It tells the engrossing story of a career military officer, his military achievements and his personal life. Soft spoken Roger Livesey plays the character of Clive Wynne-Candy, ageing on-screen over four decades, from his days as a Lieutenant in 1902 until his return from retirement during World War II. Wynne-Candy is an eccentric character, frequently at odds with his superiors and peers on account of his seemingly whimsical decisions, which in fact are driven by a sharp tactical mind and strong moral code. Deborah Kerr, at the tender age of 21, was cast as three different characters, each playing a significant role in Wynne-Candy’s life over the years. This film is a product of its time, capturing the essence of British military gentry during the first half of the 20th century; irrespective of one’s opinion of British foreign policy during this period, this film is a must-watch for cinephiles for its story of a life fully lived.

Black Narcissus (1947): Black Narcissus is an adaptation of a 1939 novel exploring the efforts of a convent in setting up a school in a remote Himalayan kingdom. Faced with a barrage of cultural barriers and distractions, the nuns become increasingly unstable and emotionally disturbed. One of them in particular, Sister Ruth (played by Kathleen Byron in an extraordinary performance), starts lashing out at her colleagues and becomes desperate to leave the nunnery, while Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) tries to maintain order and decorum among the group. It was Kerr’s second film with Powell/Pressburger after The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, and soon after, she would cross over to Hollywood and superstardom. Indian-born actor Sabu plays a notable role as the local prince, a few years after he made a splash in the films The Thief of Bagdad and Jungle Book. Besides the incredible acting performances, the film features Oscar-winning colour cinematography by Jack Cardiff. The mountainous locales are breathtaking, and I was amazed to learn that none of it was shot on location, but done entirely through camera trickery involving matte paintings and scale models.

Destry Rides Again (1939): There have been three different films bearing this title, all supposedly adaptations of the 1930 Max Brand novel. This middle version only borrows the novel’s name but features a completely different story; however, the classic pairing of James Stewart and Marlene Dietrich makes this the one to watch. Stewart plays Tom Destry, a newly arrived deputy lawman in an unlawful town, whose pacifist approach makes him the object of ridicule. However, an iron hand lurks under the velvet glove and soon the chief baddie (played by Brian Donlevy) realizes he has to resort to strong arm tactics to get rid of Destry. Marlene Dietrich gets top billing in the film as the saloon singer/gangster’s moll with a heart of gold, although by this time her star was on the wane in Hollywood. Director George Marshall had directed three Laurel and Hardy films in the early 30’s and certainly knew how to create an entertaining blend of comedy and action.

In Old Chicago (1938): The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 provides the framework for this highly fictionalized account of the real-life O’Leary family, from whose barn the fire is alleged to have originated, as per some historical accounts. The first two-thirds of the film concerns itself with the rising fortunes of the O’Leary brothers, particularly the hustler Dion O’Leary (played by heartthrob Tyrone Power) and his rivalry with businessman Gil Warren (Brian Donlevy, in one of his standard villainous roles). The action-filled third act depicts the city-wide conflagration, with the burning homes, crowds and chaos acting as the backdrop for the showdown between O’Leary and Warren. Although the film purports to be based on real-life events, most of the names and incidents are fictitious, and this is essentially a formulaic Hollywood Golden Age film with music, romance and action. Director Henry King was a reliable filmmaker for 20th Century Fox studios, making a number of successful and well regarded films with Tyrone Power (Jesse James, The Black Swan) and later with Gregory Peck (Twelve O’Clock High, The Gunfighter).

Sound of the Mountain (1954): Setsuko Hara is well known for her roles as the good-natured and frequently self-sacrificing wife/daughter in a number of films by Japanese master Yazujiro Ozu (hence her nickname, the “Eternal Virgin”). She also appeared in similar roles in a couple of films for another iconic Japanese director, Mikio Naruse, who specialized in downbeat social dramas. Sound of the Mountain is adapted from a novel by Nobel Prize winner Yasunari Kawabata, and stars Ms. Hara as a woman living in an unhappy marriage with a philandering husband. The key difference in this drama, compared to her other on-screen roles, is that her character demonstrates resolve and agency, rather than conforming to social norms. Prolific character actor, Sō Yamamura plays a key role as her father-in-law, who loves her as a daughter and provides emotional support. The mid-1950’s proved to be director Naruse’s most successful period, as he followed up this film with his two most celebrated works – Late Chrysanthemums and Floating Clouds (both of which I have yet to watch!).

House of Bamboo (1955): Samuel Fuller‘s diverse film repertoire included Westerns, war dramas and noirs. House of Bamboo is a crime drama released midway during Fuller’s prolific run in the 1950’s, when he was directing a film every year, and in some cases working on multiple productions at the same time. During his career, Fuller made a few films set in Asia (Steel Helmet and Fixed Bayonets! in Korea, China Gate in Vietnam and Merrill’s Marauders in Burma), and this one, House of Bamboo, takes place in Japan. Of course, the protagonists in all these Asia-set films were white men (no other sort of movie could get made for US audiences at that time). The story revolves around a group of ex-US military servicemen who have set up a criminal gang in Tokyo, and the attempt by an undercover Army investigator to infiltrate them. Robert Ryan continues his streak of playing menacing baddies while Robert Stack is the undercover investigator. DeForest Kelley, better known as Dr. McCoy from Star Trek, has a role as one of the gang members. Other than the novelty of the overseas setting, this is a by the numbers 1950’s crime drama, although the end product is elevated by the performances of Ryan and Stack.

Leave Her to Heaven (1945): Gene Tierney is chilling in her portrayal of a beautiful socialite who marries a successful novelist after a whirlwind romance, and then reveals the dark side of her romantic obsession. I was reminded of similar characters played by Ida Lupino in They Drive By Night (1940), Jean Simmons in Angel Face (1952), Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction (1987) and Rosamund Pike in Gone Girl (2014). What made this film notable at the time of its release is that it is scripted as a film noir, but shot like a glossy Douglas Sirk melodrama, filmed in glorious Technicolor (for which cinematographer Leon Shamroy won an Oscar). Tierney’s character Ellen Berent, is breathtakingly beautiful in every shot, which only makes her scheming, manipulative behaviour all the more shocking. Her performance garnered a Best Actress Oscar nomination, one of the highlights of a successful career which included hits like Laura, Heaven Can Wait and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir.

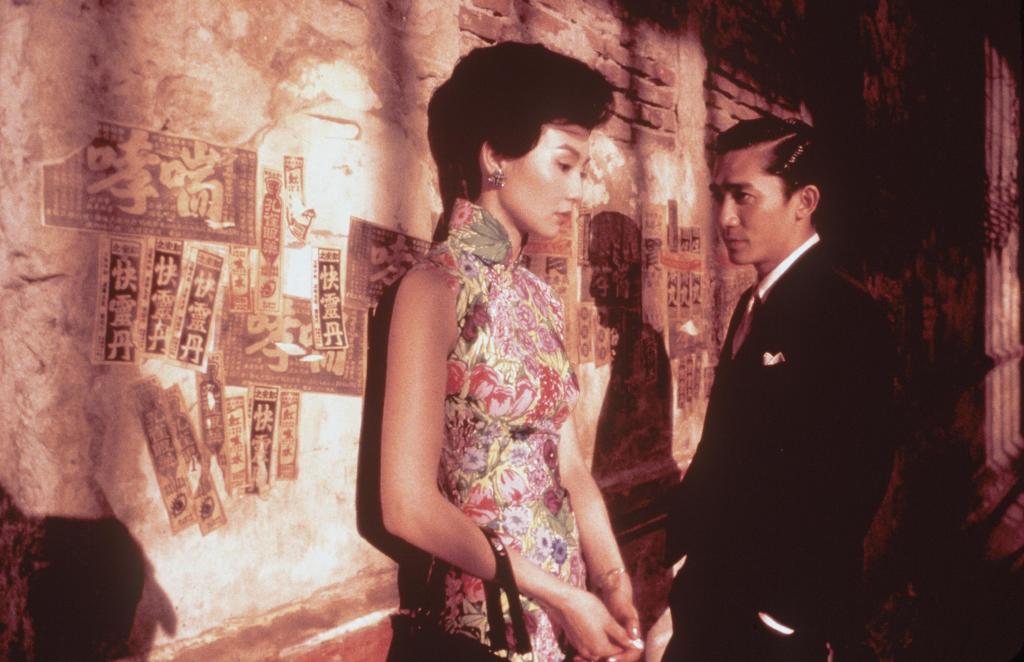

In the Mood for Love (2000): This stunningly shot romantic tale of love and longing features Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung as star-crossed lovers in 1962 British Hong Kong. In their period costumes and hairdos, they rank among the best looking romantic pairs ever seen on screen, in the same league as Alain Delon/Monica Vitti in L’Eclisse, Penelope Cruz/Javier Bardem in Jamon Jamon and Jean-Louis Trintignant/Anouk Aimee in A Man and a Woman. The heart tugging and evocative performances by Cheung and Leung, plus the stylish and atmospheric look created by cinematographer Christopher Doyle’s stark lighting and dark shadows, are the highlights of this modern classic; every scene aches with desire and melancholy. Director Wong Kar-Wai had to feverishly sort through hours of footage to complete the film in time for its debut at Cannes; among the scenes left on the cutting room floor is this one of the pair dancing in a hotel room…probably discarded because it was too lighthearted, it nevertheless gives a sense of their natural chemistry. Sofia Coppola credited the film as a key inspiration for Lost in Translation and named Wong Kar-Wai when accepting her Oscar for best original screenplay.

Here are the links to the previous thumbnails: #1-10, #11-20, #21-30, #31-40, #41-50, #51-60, #61-70, #71-80, #81-90, #91-100, #101-110 and #111-120.

One thought on “A Criterion Channel journey, films #121-130”